Now Reading: What Did Carl Sagan Warn Us About Before He Died?

-

01

What Did Carl Sagan Warn Us About Before He Died?

What Did Carl Sagan Warn Us About Before He Died?

Introduction

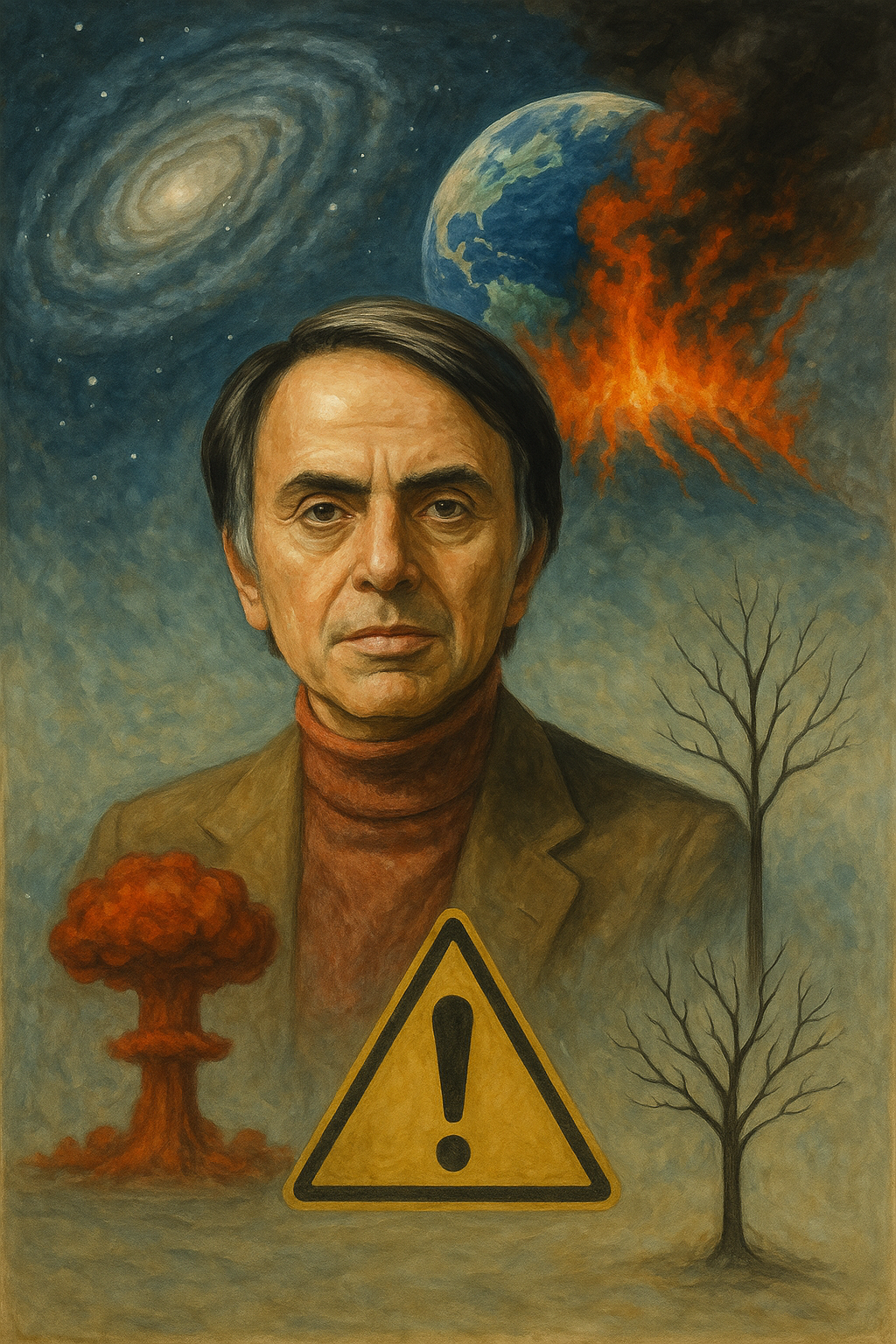

Carl Sagan (1934–1996), the famed astrophysicist, planetary scientist, author, and science communicator, was much more than the voice behind Cosmos. As a public intellectual, he used his final years not to celebrate past achievements, but to issue stark warnings for the future of humanity. These concerns ranged from nuclear annihilation and climate collapse to scientific illiteracy and political manipulation. Today, his warnings echo louder than ever, sounding both prescient and urgent in our increasingly complex world.

1. The Catastrophic Threat of Nuclear Winter

1.1 Sagan’s Role in the TTAPS Model

Carl Sagan was a central figure in raising awareness about the concept of nuclear winter—a phenomenon theorized in the 1980s that a large-scale nuclear war would ignite firestorms capable of injecting soot into the stratosphere, blocking sunlight, and devastating global agriculture. As one of the co-authors of the TTAPS study (named for Turco, Toon, Ackerman, Pollack, and Sagan), he brought scientific rigor and public visibility to this potential apocalypse.

1.2 Public Warnings and Testimony

Sagan testified before Congress in 1985, stating unequivocally that the environmental consequences of nuclear war would not be confined to the battlefield. Even a “limited” exchange could destabilize ecosystems, collapse food supplies, and kill billions. His position was controversial at the time, yet his predictions have since been reinforced by updated climate models showing how even small-scale nuclear conflicts—such as between India and Pakistan—could cause global cooling and famine.

2. The Greenhouse Effect and Climate Change

Well before climate change became a political flashpoint, Sagan was sounding the alarm. He famously compared Earth’s potential future to that of Venus, a planet with a runaway greenhouse effect that led to surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead. Speaking to Congress, he explained that even modest increases in carbon dioxide on Earth could tip the climate into instability.

Sagan emphasized that humans were altering the planet’s atmosphere at a dangerous pace, and that early action was essential. He connected the dots between fossil fuel emissions, rising temperatures, and the long-term habitability of the Earth—decades before climate discourse entered the mainstream.

3. The Dangers of Scientific Illiteracy

Perhaps one of Sagan’s most chilling warnings was cultural, not environmental. In his book The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark—published shortly before his death—he wrote:

“We live in a society exquisitely dependent on science and technology, in which hardly anyone knows anything about science and technology.”

Sagan feared that without scientific literacy, the public would fall prey to charlatans, conspiracy theorists, and authoritarian figures who manipulated fear and ignorance for control. His words read like a prophecy in today’s age of misinformation, anti-science rhetoric, and political tribalism.

4. Political Tribalism and the “Reptile Brain”

Sagan frequently spoke about how human evolution made us vulnerable to tribal thinking. He warned that modern politics often exploited our primal instincts—what he called the “reptilian brain.” Fear, in-group bias, and aggression were evolutionary holdovers that, when combined with modern propaganda and mass media, could lead societies toward irrational and dangerous decisions.

He didn’t just call for scientific thinking, but for emotional maturity—a recognition that empathy, reason, and evidence must overcome fear and ideology.

5. Asteroid Impacts and Planetary Defense

While nuclear war and climate change topped Sagan’s warning list, he also consistently pushed for the global community to take seriously the threat posed by near-Earth objects (NEOs)—asteroids and comets capable of causing extinction-level events.

He supported space-based tracking systems and proposed that humanity should develop the means to deflect incoming objects. However, he also warned of the dual-use nature of such technologies, noting that the same methods for deflecting asteroids could be weaponized. The key, he insisted, was international cooperation and transparent scientific governance.

6. Extraterrestrial Contact and SETI Caution

Although Sagan was a strong supporter of the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), he remained cautious about how we should approach contact. He warned that broadcasting our existence to the cosmos without understanding the potential risks could be dangerous. He advocated for listening more than transmitting and believed any future interaction with alien civilizations must be approached with humility, not hubris.

He compared early human contact between civilizations—often resulting in domination or genocide—to caution that first contact on an interstellar scale might carry similar risks.

7. Modern Relevance of Sagan’s Warnings

7.1 Nuclear Risks Still Exist

Even after the Cold War, thousands of nuclear weapons remain on high alert. The resurgence of geopolitical tensions and modernization of arsenals make Sagan’s nuclear winter warnings chillingly relevant. A single conflict could still plunge the Earth into ecological catastrophe.

7.2 Climate Crisis Is Escalating

In 2025, global temperatures are already 1.2°C above pre-industrial levels. Sagan’s early calls for sustainability and reduced fossil fuel use have gone unheeded by many governments. Extreme weather, rising seas, and mass displacement are proving his fears well-founded.

7.3 Scientific Skepticism Is Under Siege

From vaccine denial to climate change denial, Sagan’s concern about scientific illiteracy has manifested across the world. The rejection of expert consensus in favor of online echo chambers threatens public health, democratic governance, and our ability to respond to existential threats.

8. Carl Sagan in His Own Words

“The nuclear arms race is like two sworn enemies standing waist deep in gasoline, one with three matches, the other with five.”

“We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.”

“Science is more than a body of knowledge. It’s a way of thinking—a way of skeptically interrogating the universe.”

Sagan’s blend of poetic language and scientific rigor made his warnings unforgettable—and accessible to everyone from presidents to schoolchildren.

9. Final Legacy

Carl Sagan died of pneumonia (related to bone marrow disease) in 1996, but his legacy lives on. His wife and collaborator, Ann Druyan, continues his work through the Cosmos series and science advocacy. His writings remain required reading for those seeking to understand not just the universe—but how to survive within it.

His warnings were not doomsday prophecies, but roadmaps. He never preached despair—he offered tools for hope: education, empathy, evidence-based reasoning, and above all, curiosity.

Conclusion

What did Carl Sagan warn us about before he died? He warned us about ourselves. Our capacity for destruction. Our tendency toward ignorance. Our failure to appreciate the fragility of our planet and the power of our minds.

Yet he also reminded us that the same species capable of launching nuclear missiles is capable of launching satellites to Saturn. The same brain that creates warheads also crafts poetry, paints nebulae, and dreams of Mars.

In remembering Carl Sagan’s warnings, we’re not just preserving a voice from the past—we’re choosing a path for the future.